The reviews for the new M1 MacBooks are here and they’re spectacular. They’re not just faster than the previous Intel machines, they’re among the fastest Apple laptops ever made, with some tests besting even the flagship 16-inch MacBook Pro. And I really, really want one.

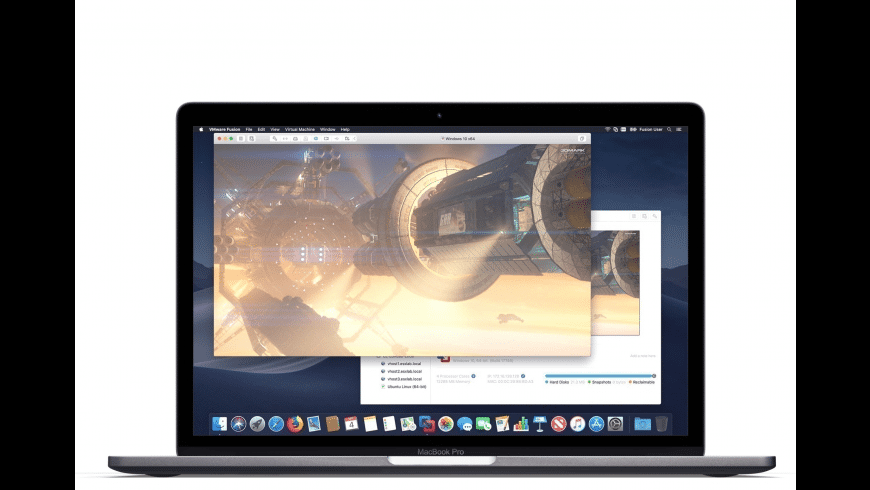

VMWare Fusion for M1 Mac has not officially been announced, but we have found out via Twitter that it is currently a work-in-progress and we can expect updates soon. VMWare Fusion is one of the two. M1 Macs and Horizon For VMware Horizon customers, the product management team has tested the Horizon Client on M1 devices, and has verified that it works very well, thanks to Rosetta 2. So, if you have any early adopters in your BYOD fleet and you’re expected to support anything that walks in the door, you should be okay. Also note that while you then will be able to run virtual machines on your M1 mac, it will still not run virtual machines that require an intel or amd processor. There's some talk that intel processor emulation is being investigated by VMware, but if and when that happens is unsure. Here's another thread on the subject. VMware Fusion: Powerfully Simple Virtual Machines for Mac. VMware Fusion Pro and VMware Fusion Player Desktop Hypervisors give Mac users the power to run Windows on Mac along with hundreds of other operating systems, containers or Kubernetes clusters, side by side with Mac applications, without rebooting.Fusion products are simple enough for home users and powerful enough for IT.

I’ve made no secret of my intention to hold off on buying a new Mac until Apple started using its own silicon inside, and the day finally arrived. The Apple Store was down, the event clock was ticking down, and I was ready to buy my first new MacBook in nearly a decade.

Except I’m not. At least not yet, anyway. While there’s a lot to like about the speed and battery life claims in the new M1 chip in the MacBook Air and MacBook Pro, there are just as many reasons to hold off on the purchase, especially if you’re coming from an older high-end machine. It’s not so much that I’m disappointed with the first M1 Macs as much as my curiosity is piqued.

In a nutshell: I want what’s coming next.

My issue isn’t with the design, which is a carbon copy of the Intel models. Sure, an edge-to-edge screen would be nice, as would a smaller footprint, Face ID, light-up Apple logo, and MagSafe integration, but the current design is plenty nice.

While there’s no doubt that these machines are crazy fast for their prices—though there’s some doubt that they’re faster than the 98 percent of PCs as Apple claims—there’s also reason to believe that Apple is only scratching the surface with what it will deliver.

Take the ports. On the previous MacBook Pro lineup, Apple offered a $1,799 step-up option that delivered four USB-C type Thunderbolt 3 ports rather than two on the base model. That’s the configuration of my work machine and I use every one of the ports on a daily basis, as do a lot of users. But like the MacBook Air, the new M1 MacBook Pro and Mac mini only have two Thunderbolt 3/USB 4 ports.

That’s likely because the M1 chip only has a single Thunderbolt 3 controller—which also explains why both ports are on the same side—but it also means you can’t buy an M1 Mac without being seriously hampered when it comes to USB ports. Assuming you’re using one for charging, you’re probably going to need a hub, which is an inelegant solution.

Future MacBook Pro models, even smaller ones, aren’t likely to have this restriction. Apple clearly understands that pro users need more than two Thunderbolt ports, which is why the 4-port Intel models are still on sale, for the same prices as before. Apple wouldn’t have kept those aging Intel machines around if it didn’t recognize the need for more ports, and I expect next year will bring M1 models with twice as many ports.

Ports aren’t the only thing that’s lacking with the new Macs. They’re also capped at 16GB of RAM, the same limitation that the previous low-end models they replace had. Granted, 16 gigs isn’t a small amount, but it’s less than what power users want.

Here again, Apple understands the demand for more RAM and offers a 32GB upgrade for $400 in the higher-end Intel models. That’s not a terrible price, but you’re also being forced to choose between speed and memory. Early Geekbench benchmarks give the M1 a single-core score of 1630 and a multi-core score of 7220 compared to 1260 and 4480, respectively, on the still-shipping 2.0GHz Core i5 MacBook Pro. Even if those numbers are off by a magnitude of 10, the M1 is still significantly faster, with or without the extra RAM.

Vmware Mac M1

Tick, tock

But even if you don’t need more than 16GB of RAM, it’s still wise to wait. While we don’t quite know how fast the M1 chip in the MacBook Air is compared to the one in the MacBook Pro, but we can assume it has a higher clock speed and sustained performance, if for no other reason than the Pro has a fan for cooling while the Air doesn’t.

As Apple describes it, the fan in the Pro is needed to “sustain blazing-fast performance,” while the Air uses an aluminum heat spreader to dissipate heat and deliver “amazing performance without a fan.” While both machines will deliver tremendous speed boosts over the predecessors, it’s pretty clear that the M1 in the Pro runs hotter and, by extension, faster.

And these chips are likely only a small part of what Apple will deliver with its M chips. Based on the speed tests for the latest Intel MacBook Pros, there’s a wide gap between the entry-level and the step-up models. Using the industry-standard Cinebench R20 benchmark, the 1.4GHz Core i5 scored 397 (single-core) and 1616 (multi-core), while the 2.0GHz model posted 436 and 1929, respectively. That’s a decent speed boost, and along with the lack of ports and RAM, it’s clear that an M2 or M1Z chip is on the horizon.

And that’s the model I’m waiting for. Rumors have claimed that there are 14-inch and 16-inch Macbook Pros in the works, and I fully expect them to deliver the specs I’m looking for, along with the massive speed boosts Apple has already delivered. And who knows, maybe we’ll even get a decent FaceTime camera by then too.

With the newly released M1 Macs, there have been lots of questions about being able to run other operating systems on it, particularly from developers that are used to running Window or Linux in Virtual Machines using virtualization on their Intel Macs. So what challenges do the M1 Macs bring in this regard?

If you are new to all this, it is important to understand the parts involved. First there are virtual machines, which act as virtual computers running on a main or host computer. Second, there are the instruction sets for the computer and OS. These virtual computers run an operating system (OS) of some kind and in most cases this OS has to have the same instruction set as the host computer. This allows the instruction to be passed through the VM to the CPU and allows for good performance. Which is what makes it so easy to run Windows 10 x86 on an Intel Mac — they both are using Intel CPUs with the same instruction sets.

But what if the instruction sets differ as they do with Intel and M1 Macs? Obviously you can no longer pass an x86 instruction to an M1 chip and expect anything to happen. So some translation or emulation needs to happen. This is typically much, much slower.

In general this is what Apple is doing with Rosetta 2 on Big Sur to allow your x86 Mac apps to run on an M1 Mac. They do an entire app translation on first launch (and also re-do it at times) and then run the translated app. This is a great technique but it doesn’t really work at a virtual machine level. And in fact, Apple specifically says that Rosetta 2 cannot be used with virtualization software.

That’s the bad news. But there are options on the horizon.

Emulation

The first option is OS-level emulation. What would happen here is that emulation software (say, QEMU, a popular open-source emulator and virtualizer) would translate x86 instructions to ARM instructions (usually on-the-fly) so that an x86 operating system could run on an M1 Mac. In theory this would allow Windows 10 x86 for example to run as a (virtual computer) on an M1 Mac.

Technically this is more than a theory since it has been done before. You may remember it was possible to run Windows 98 x86 on a PowerPC Mac back in the day using software such as Connectix Virtual PC. The downside to this approach is that it can be quite slow. Fortunately the M1 Macs are proving to be very speedy and might be able make this technique acceptable for casual use. I expect the QEMU project will be updated to eventually allow emulation of x86 operating systems on M1 Macs.

OS Vendors

You might remember in the WWDC 2020 keynote Apple showed Linux running as a virtual machine with Parallels on an M1 Mac. This demo was actually running an ARM Linux distro in that virtual machine. Since it was not an x86 distro, its usefulness depends on its ability to run the apps you need. If you wanted to run an x86 Linux app then it would not work on an ARM distro.

However, the OS vendors are working on this. Much like what Apple did with Rosetta 2, they can add OS-level support to translate individual apps from x86 to ARM, thus allowing them to work in a virtual machine. I haven’t heard of progress on this front with Linux, but I expect there will be some convoluted way to do it at some point.

Microsoft does have an ARM version of Windows, but right now it is only licensed for OEM use to include with a computer, so virtualizing it is not yet an option. And even if you could virtualize ARM Windows on your M1 Mac, it also is only useful to you if it can run the apps you want.

Currently ARM Windows has a translator that lets it run 32-bit x86 apps, but performance is poor, especially when compared to what Apple has done with Rosetta 2 in Big Sur. Microsoft has said they are working on adding the ability to run 64-bit x86 apps on ARM Windows, but that feature is not ready yet and performance is unknown.

Mac M1 Vmware Fusion Windows

I expect virtualizers such as Parallels, VMware and VirtualBox will all eventually have versions that run on M1 Macs and can run ARM operating systems, although perhaps just Linux to start. I don’t expect them to include emulators in their products.

Update (2020-4-14): Parallels has just released 16.5 with support for running Windows for ARM on M1 Macs.

When Microsoft adds 64-bit x86 translation and has it working at a decent speed and if it decides to make ARM Windows available for use in virtual machines then you would also be able to run Windows on an M1 Mac and run common Windows apps. But for now, we wait.

Update (2020-12-08): Some progress continues to be made on this. Here are some rough instructions on how to get Windows ARM running in a VM (UTM running on QEMU).

Other Options

Another option is the CodeWeavers product that is based on the WINE open-source project. This project essentially provides a translated Windows API that allows some Windows apps to run on a Mac. It does not run Windows itself, only apps, and only a small subset at that.

But because it translates the apps to essentially a Mac x86 app, they are a candidate for Rosetta 2 on Big Sur to translate. That’s a lot of levels of translation, but in the end you end up with a Windows app running on an M1 Mac.

CodeWeavers recently posted some information about their early testing of this.

Wrap Up

With all this said, if you require the ability to run an x86 version of Windows or Linux, then an M1 Mac cannot be your sole machine at this time. You’ll either want to also have an Intel Mac to run those in virtual machines or get dedicated separate hardware for them.

And if you want to make your own native apps for M1 Macs, Xojo now has the ability to create native apps for M1 Macs.